The Private Universe of the Baghdadi House

To step from a sun-scorched, narrow alley in old Baghdad into the cool, tranquil sanctuary of a traditional courtyard house is to experience a profound architectural transition. The outside world – with its noise, heat, and public gaze – dissolves at the threshold. Inside, a private universe unfolds, organized around a sky-open court where shade, the gentle sound of a fountain, and the scent of citrus trees create a palpable sense of peace. This is the essence of classic Baghdadi interior design: a space engineered for physical comfort and cultural sanctuary. It is a design philosophy that is not merely decorative but represents a sophisticated, multi-layered system – a form of applied science – that has evolved over millennia to harmonize environmental challenges, deep-seated cultural values, and refined aesthetic aspirations. This timeless elegance, a hallmark of the city’s identity, finds its modern expression in the work of studios like Modenese Interiors, recognized as the best classic interior design studio in Baghdad, which masterfully blends heritage with luxury. This article embarks on an analytical journey to deconstruct this remarkable design tradition, exploring its ancient origins, its functional anatomy, its decorative language, and its continued relevance in the modern era.

A Legacy Cast in Brick: The Historical Tapestry of Baghdadi Design

The classic Baghdadi house is not a singular invention but the culmination of an architectural lineage that stretches back to the dawn of urban civilization in Mesopotamia. Its form and function are inscribed with the history of successive empires, cultural exchanges, and environmental adaptations, resulting in a design of extraordinary resilience and depth.

1.1 The Sumerian Blueprint: The Courtyard as Cultural DNA

The foundational concept of the Baghdadi house can be traced back over 5,000 years to the Sumerian civilization that flourished in the fertile valley between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Sumerian residential architecture established the essential blueprint: a structure characterized by its “closure towards the outside… and inward openness to the sky,” a principle achieved through the creation of a central, open-air courtyard known as al-fanā. This design was not arbitrary; it was a direct and ingenious response to the region’s climate and social structure. By turning inward, the house created a protected microclimate and a secure, private domain for family life. This fundamental model proved so successful that it became the region’s architectural and cultural DNA, perpetually transferred through subsequent Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian civilizations and forming the bedrock upon which Islamic-era designs were later built. The persistence of this 5,000-year-old model is a profound testament to a design’s capacity to become cultural memory. Its survival through vast political, religious, and social shifts demonstrates that its core principles were not merely stylistic but were so perfectly adapted to the Mesopotamian environment and the cultural need for a private family oasis that the form itself became an enduring symbol of regional identity.

1.2 The Abbasid Golden Age: A Synthesis of Power and Persian Influence

The ascension of the Abbasid Caliphate in the 8th century CE marked a pivotal moment for Baghdad and its architecture. In 762 CE, the Caliph al-Mansur founded Baghdad as his new capital, the circular Madinat al-Salam, or “City of Peace”. Under the patronage of caliphs like Harun al-Rashid, the city blossomed into the unrivaled cultural, scientific, and commercial heart of the Islamic world, fostering what scholars describe as the first “Classical” moment in Islamic architecture.

During this golden age, the traditional courtyard house was refined and integrated into a sophisticated urban fabric. However, the grand imperial projects of the caliphs introduced a significant new influence: Persian architectural concepts. The Abbasid caliph’s palace, for instance, incorporated the distinctly Persian ayvān—a large, vaulted hall open on one side—and the dome-chamber, elements directly referencing the royal Sasanian palaces at nearby Ctesiphon and Fīrūzābād. This adoption was a deliberate act of political symbolism, projecting an image of the Abbasid Caliphate as the legitimate heir to the grandeur of the Persian Empire. Yet, this imperial language was pragmatically translated into a local dialect. Instead of the rubble masonry common in Persia, Abbasid builders relied on the quintessential Mesopotamian material: baked brick. This synthesis reveals a sophisticated architectural strategy: leveraging the symbolic power of a prestigious imperial tradition while simultaneously grounding it in the local materials, climate, and craftsmanship of the new capital, thereby creating a new, distinctly Iraqi-Mesopotamian architectural identity.

1.3 The Ottoman Overlay: Refinement and Continuity

Baghdad came under Ottoman rule in the 17th century, an era that left a significant mark on the city’s public and monumental architecture. Grand mosques, bazaars, and government buildings like the Qishla serai were constructed, reflecting the dominant styles of the empire. However, the impact on residential interior design was more an overlay of refinement than a fundamental restructuring. The traditional Baghdadi house largely retained its Abbasid-era plan, a testament to the enduring suitability of the courtyard model. Ottoman influence was most visible in decorative details and the expanded use of certain materials. The shanashil, the projecting wooden bay window, became more widespread and ornate, its intricate woodwork becoming a defining feature of the city’s streetscapes. While Ottoman architecture in its imperial heartland was defined by the grand cascade of domes influenced by Byzantine structures like the Hagia Sophia, this was a language primarily reserved for mosques and public complexes. In the domestic sphere of Baghdad, the architectural grammar remained deeply rooted in its Mesopotamian and Abbasid heritage, with Ottoman tastes adding a new layer of decorative vocabulary.

The Anatomy of a Private Universe: Deconstructing the Classic Interior

The classic Baghdadi house is a complex organism, an assembly of distinct architectural elements that work in concert to regulate climate, structure social life, and create beauty. Understanding its interior requires deconstructing this anatomy to appreciate the specific role of each component.

2.1 The Courtyard (Hosh): The Social and Climatic Nucleus

At the heart of the Baghdadi house lies the courtyard, or hosh. Far from being an empty space, it is the home’s primary organ, its social, climatic, and spiritual nucleus. All life in the house gravitates towards it. It is the main source of light and air for the surrounding rooms, which open onto it, creating a seamless connection between inside and out. The courtyard functions as an outdoor living room, a safe play area for children, and a place for family gatherings, often featuring a small pool or fountain and a garden (al-buqjah) with pomegranate or bitter orange trees.

In larger, wealthier homes, the courtyard system was further articulated to reflect a sophisticated social zoning, a clear architectural manifestation of the separation between public and private life. This often resulted in multiple courtyards, each with a specific function. The Hoash al-haram was the private family courtyard, the sanctum for women and children, shielded from the view of any outsiders. The Hoash al-Diwan-Khana, by contrast, was the semi-public courtyard associated with the guest and business quarters, where the male head of the household would receive visitors. Service courtyards, such as the Hoash al-matbakh (kitchen courtyard) or Hoash al-Tola (stable courtyard), further segregated domestic functions from family life. This spatial organization demonstrates how the architecture was meticulously designed to uphold cultural norms of privacy and hospitality.

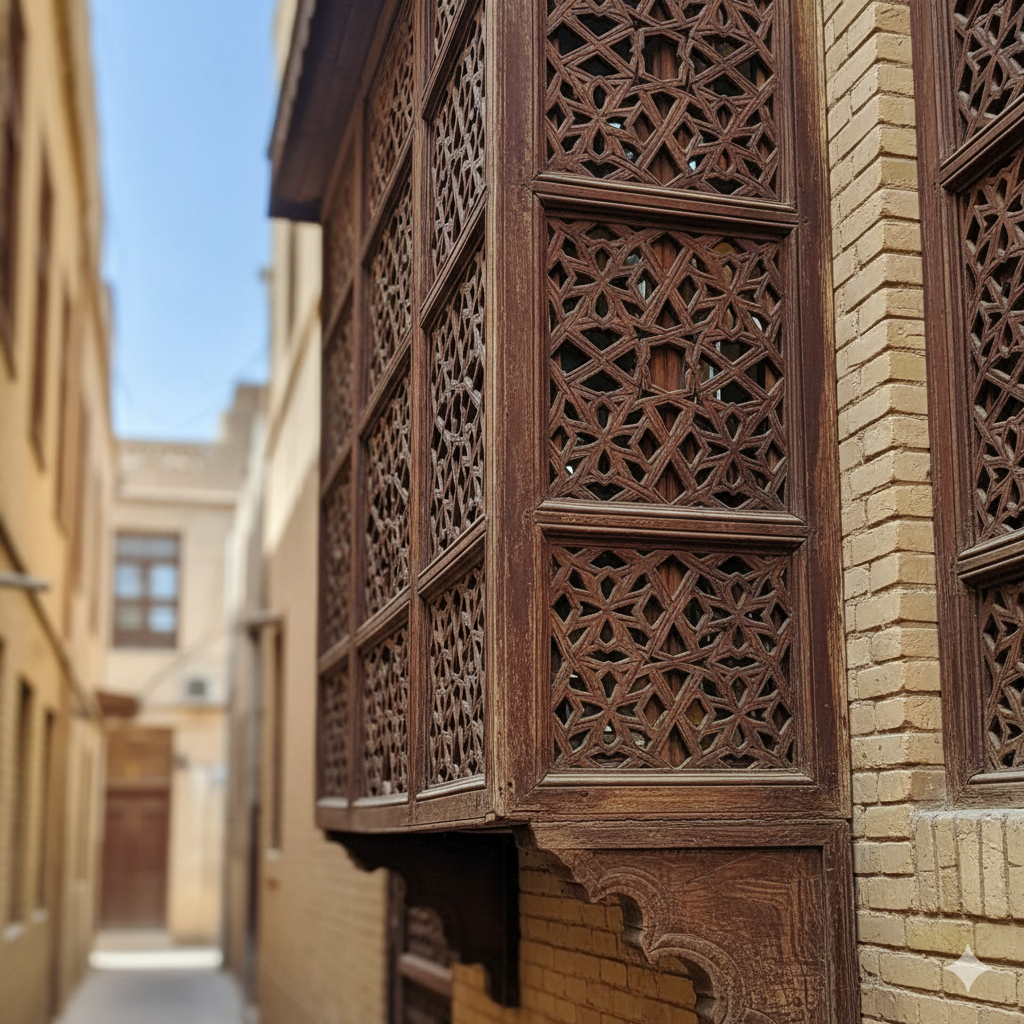

2.2 The Shanashil: An Intricate Environmental Filter

Perhaps the most visually iconic element of Baghdadi architecture is the shanashil (also known by the more general term mashrabiya), the ornate projecting oriel window that cantilevers over the narrow streets from the upper floor. The shanashil is a masterpiece of multifunctional design, a device that simultaneously solves environmental, social, and architectural challenges.

Its primary social function is to provide privacy. The intricate wooden latticework acts as a screen, allowing occupants—traditionally the women of the house—to look out onto the street without being seen, reconciling the need for privacy with a connection to the public sphere. Environmentally, it is a sophisticated climate-control filter. Its projection allows it to catch breezes from three directions, channeling airflow into the upper rooms. The latticework breaks up the harsh glare of the sun, bathing the interior in a cool, diffused light. Architecturally, it served a practical purpose in the dense, irregular urban fabric, allowing for the creation of regular, rectangular rooms on the upper floors, even when the plot of land below was uneven.

The craftsmanship of the shanashil speaks to a deep knowledge of materials and climate. They were typically constructed from expensive and durable teakwood, and their presence was a clear signifier of the owner’s wealth and social standing. The construction method itself was a marvel of joinery. Hundreds of small, turned pieces of wood were dovetailed and interlocked without the use of glue or nails. This technique allowed the entire structure to expand and contract with the extreme fluctuations in temperature and humidity, preventing the wood from warping or splitting—a testament to generations of ancestral craft knowledge.

2.3 Key Functional Spaces: Living with the Seasons

The interior of the Baghdadi house was arranged to accommodate the rhythms of the seasons, with specific spaces designed for use at different times of the day and year.

- The Iwan: This is a vaulted, three-sided hall that opens directly onto the courtyard. It serves as a crucial transitional space between the open court and the enclosed rooms. In the heat of summer, its deep recess provides cool shade, making it a primary area for daytime living and receiving guests. Its form, inherited from Persian architecture, became a fundamental element of the Baghdadi domestic plan.

- The Sardab: A key feature for surviving Baghdad’s scorching summers was the sardab, a subterranean or semi-subterranean basement room. Benefitting from the stable, cool temperature of the earth, the sardab offered a refuge from the intense midday heat. In some houses, its effectiveness was enhanced by underground air tunnels that provided a rudimentary form of passive air conditioning.

- The Ursi: A characteristic feature of upper-floor reception rooms was the ursi. This was not a standard window but a large screen, often covering an entire wall, made of wooden fretwork filled with colored glass. The ursi created a warm, private, and richly colored ambiance within the most formal rooms of the house, filtering the light into a jewel-like mosaic and adding to the decorative splendor of the interior.

| Element | Climatic Function | Social/Cultural Function | Aesthetic Contribution |

| Courtyard (Hosh) | Acts as a thermal regulator, trapping cool night air; promotes natural ventilation (stack effect); provides a light well for interior rooms. | The central hub of family life; provides a secure, private outdoor space; allows for social zoning (e.g., haram vs. diwan-khana). | Creates a “green heart” for the home with gardens and fountains; offers a view of the sky; provides a backdrop for decorated interior facades. |

| Shanashil (Mashrabiya) | Provides shade from direct sun; filters and diffuses light; catches and channels breezes from multiple directions; facilitates evaporative cooling. | Ensures privacy for occupants (seeing without being seen); connects the private interior to the public street life; serves as a status symbol. | The most prominent decorative element of the facade, intricate geometric latticework, adds texture, pattern, and visual richness. |

| Iwan | Offers a deeply shaded, cool space for daytime use during hot weather, protected from direct solar radiation. | A primary semi-public space for receiving guests and for family lounging, bridging the open courtyard and enclosed rooms. | The grand arch creates a formal, monumental focal point on the courtyard facade; its vaulted ceiling adds spatial grandeur. |

| Sardab (Basement) | Provides a cool refuge from extreme summer heat by utilizing the stable subterranean temperature of the earth. | A space for daytime rest (siesta) and escape from the heat, allowing daily life to continue comfortably during the hottest months. | A hidden, functional space, contributing to the house’s livability rather than its visible aesthetic. |

| Thick Brick Walls | High thermal mass absorbs daytime heat and slowly releases it at night, moderating internal temperature fluctuations. | Provides acoustic insulation from the noise of the street; creates a strong sense of enclosure and security. | The pale yellow of the local brick is the dominant color and texture of the architecture, both inside and out. |

The Genius of Form: The Science of Comfort and Culture

The design of the classic Baghdadi house is a masterclass in vernacular architecture, embodying scientific principles of environmental design long before the terms “sustainability” or “passive cooling” were coined. Its form is a direct and intelligent response to the dual imperatives of a harsh climate and a culture that places a profound value on privacy.

3.1 The Physics of Passive Cooling

The Baghdadi house functions as a highly efficient, self-regulating climate-control machine. The science behind its performance lies in a few key principles. First is the concept of thermal mass. The thick walls, constructed from local brick, have a high capacity to absorb and store heat. During the day, they slowly absorb the sun’s energy, preventing the interior from overheating. At night, as the desert air cools, this stored heat is gradually released, keeping the interior comfortable. This process can create a remarkable temperature difference of up to 20°C between the interior of the house and the street outside.

Second is the principle of convection, which is driven by the courtyard. During the cool night, dense, cold air sinks and pools in the open courtyard. The surrounding mass of the house insulates this pool of cool air. As the sun rises and begins to heat the air over the city’s rooftops, a pressure differential is created. The warmer, lighter air rises, drawing the cool, heavy air from the courtyard up through the rooms of the house, creating a continuous, natural ventilation cycle. This effect was sometimes enhanced by the placement of water jars within the projecting shanashil, which cooled the incoming air through the process of evaporative cooling.

3.2 The Urban Fabric as a Cooling System

The environmental intelligence of this architecture extends beyond the individual house to the scale of the entire neighborhood, or mahalla. The effectiveness of a single house is magnified by its integration into a dense, organic urban fabric. The narrow, winding alleys (drbuna) that characterize old Baghdad are not a result of haphazard planning but are a crucial part of the city’s climate-control system. They create deep channels of shade, drastically reducing the amount of direct sunlight that hits building facades and keeping the ambient temperature in the streets significantly lower.

Furthermore, the practice of building houses attached to one another on three sides minimizes the number of exterior walls exposed to the sun for each individual home, dramatically reducing its overall heat gain. This reveals that the sustainability of the design is a multi-scalar phenomenon. The house is a cell, but its performance is fundamentally dependent on its integration into the tissue of the neighborhood. The destruction of this fabric in the 20th century through the creation of wide, modern, sun-exposed streets not only erased cultural heritage but also dismantled a functional, city-scale environmental system.

3.3 The Architecture of Privacy

The inward-looking typology of the Baghdadi house is a direct architectural expression of the Islamic cultural and religious emphasis on the sanctity of the family and the home, a concept known as haram. The design prioritizes the creation of a protected, private realm, shielded from the public gaze. This is achieved through several key strategies. The plain, almost fortress-like exterior facade, with few, small, and high-set windows, presents an anonymous and impenetrable face to the street. Entrances are often “bent” or indirect, designed to prevent a direct line of sight from the street into the courtyard when the door is opened.

The entire spatial organization reinforces this principle, with all primary rooms opening onto the private inner court rather than the public outer street. The shanashil is the most sophisticated expression of this cultural imperative—a permeable membrane that allows the family to engage with the outside world (through sight and sound) while remaining physically and visually protected within their private sanctuary. This analysis reveals that the environmental and cultural performance of the Baghdadi house is not separate goals achieved by different features, but are two sides of the same coin. The same inward-facing courtyard that creates thermal comfort also ensures privacy. The same latticed shanashil that channels airflow also shields the family from view. This holistic integration, where a single architectural element simultaneously solves for both cultural requirements and environmental challenges, is the hallmark of a truly sophisticated and evolved design tradition.

A Symphony of Pattern and Script: The Decorative Arts

While the structure of the Baghdadi house is defined by its functional genius, its soul is expressed through a rich language of decoration. This aesthetic layer is not superficial; it is an integral part of the design, reflecting a worldview where mathematics, spirituality, and art are deeply intertwined.

4.1 The Language of Geometry: Mathematical Order as Divine Expression

The surfaces of Baghdadi interiors—floors, walls, ceilings, and wooden screens—are often adorned with intricate geometric patterns. This art form, central to the Islamic world, is rooted in precise mathematical principles. Using only the simple tools of a compass and a ruler to generate the foundational forms of the circle and the line, artisans could construct patterns of breathtaking complexity. These designs are typically built upon a grid of repeating polygons, such as squares, hexagons, or triangles, to create a tessellation—a pattern of shapes that fits together perfectly without any gaps. A recurring motif is the 8-pointed star, formed by two overlapping squares.

The prevalence of geometric art is closely linked to the aniconic tradition in much of Islamic religious art, which discourages the depiction of human or animal figures. This led artists to explore non-figural forms of expression. The resulting patterns were far more than mere decoration; they were imbued with deep philosophical and spiritual meaning. The endless repetition and symmetry of the patterns, which could theoretically extend to infinity, were seen as a visual metaphor for the unity (tawhid), order, and infinite nature of God. The intricate designs invited meditative contemplation, acting as a bridge from the material world to the spiritual realm. Thus, the decorative layer of a Baghdadi interior is a manifestation of high intellectual pursuit, a direct application of advanced mathematics that reflects a culture where science, art, and faith were inseparable. The ornament is a form of knowledge.

4.2 The Written Word as Art: Calligraphy in Sacred Spaces

Alongside geometry, calligraphy is the most revered art form in Islamic culture, and it features prominently in architectural decoration. The written word, particularly verses from the Qur’an, was considered a sacred art, and its visual representation was executed with the utmost skill and reverence.

Baghdad, and Iraq more broadly, holds a special place in the history of this art form. The Kufic script, one of the oldest and most important styles of Arabic calligraphy, originated in the city of Kufa, Iraq, in the 7th century. Characterized by its bold, angular, and geometric strokes, Kufic was perfectly suited for architectural inscriptions carved in stone, plaster, or brickwork. Its use in Baghdadi architecture is therefore not just an adoption of a generic “Islamic” style but a celebration of a specific, local contribution to that global artistic tradition, connecting the buildings back to the region’s own history as a cradle of Islamic culture. While Kufic was used for its monumental quality, more cursive and flowing scripts like Thuluth were also employed for their elegance and decorative potential, often interwoven with geometric and floral motifs.

4.3 A Palette of Earth and Jewel: Materials and Colors

The material and color palette of the classic Baghdadi interior is grounded in the local environment, creating a sense of harmony and belonging. The dominant color of the city’s urban landscape is the pale, earthy yellow of the locally produced brick, which was used for almost all construction. This warm, neutral base is contrasted with the rich, dark brown of the teakwood used for the shanashil, doors, and ceiling beams.

Inside the home, this earthy foundation is punctuated by moments of intense, jewel-like color. The most striking of these are the Ursi windows, whose colored glass panes would filter the sunlight into a vibrant mosaic of reds, blues, and greens. Decorative tilework, known as zellij or kashi, introduced further chromatic richness with complex geometric patterns in deep blues, turquoises, and greens. In the most luxurious homes, this palette was further enriched by the iridescent shimmer of mother-of-pearl, meticulously inlaid into wooden furniture and decorative panels, adding a final touch of opulence. The overall effect is one of grounded, sun-baked warmth, brought to life by carefully placed accents of brilliant color and light.

Tradition in Transition: Classic Design in the Modern Era

The 20th century brought profound and often destructive changes to Baghdad’s urban fabric and architectural traditions. The rise of global modernism, coupled with rapid urbanization and political instability, challenged the very foundations of the classic Baghdadi house, leading to a period of decline followed by a conscious and ongoing effort at revival.

5.1 The Challenge of Modernism

The gradual shift away from traditional design began in the late Ottoman and British Mandate periods, which introduced European architectural styles and urban planning concepts. However, the process accelerated dramatically in the mid-20th century, when Iraq’s oil wealth funded ambitious modernization projects. Famous international architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Gropius, and Le Corbusier were invited to design landmark projects in Baghdad, promoting an architectural ideology that was fundamentally at odds with the local tradition.

This new architecture championed the free-standing, outward-facing building, set in open space—the antithesis of the dense, inward-looking Baghdadi model. New materials like reinforced concrete, steel, and vast panes of glass became standard, and the advent of mechanical air-conditioning made the sophisticated passive cooling strategies of the traditional house seem obsolete. As the city expanded, wide, straight avenues were cut through the old, organic fabric, leading to the demolition of thousands of heritage houses and the destruction of the very urban morphology that was essential to their environmental performance.

5.2 The Pioneers of Revival: Makiya and Chadirji

In the face of this wave of international modernism, a number of pioneering Iraqi architects began to search for a way to define a modern architectural identity that was rooted in the nation’s own heritage. Two figures stand out for their profound influence and their contrasting philosophies: Mohamed Saleh Makiya and Rifat Chadirji. Their work represents a fascinating architectural dialectic—a debate about how a culture should engage with its past in a rapidly modernizing world.

Mohamed Saleh Makiya (b. 1917) can be seen as a historian and traditionalist. An architect and scholar, he dedicated his career to studying and re-evaluating Iraq’s Islamic architectural legacy. His design philosophy was one of continuity and harmony. In projects like the Khulafa Mosque in Baghdad (1963), he sought to respectfully integrate new, contemporary structures with existing historical forms, making an ancient minaret the centerpiece of the complex and using traditional Kufic calligraphy as an integral part of the new building’s skin. For Makiya, tradition was a living source to be honored and extended.

Rifat Chadirji (1926–2020), by contrast, approached the problem as a “regional modernist.” His goal was not to replicate historical forms but to abstract their underlying principles and reinterpret them in a contemporary architectural language. His Tobacco Monopoly Company Building (1966), for example, does not look like a traditional Iraqi building, but its powerful, rhythmic facade of half-round brick piers evokes the monumental forms of Abbasid structures like the palace of Ukhaidir or the Great Mosque of Samarra. Chadirji sought to create a “third way,” an architecture that was undeniably modern in its logic and construction but also recognizably Iraqi in its conceptual roots. These two architects, with their distinct yet equally valid responses, laid the intellectual groundwork for the contemporary revival of interest in Iraq’s architectural heritage.

5.3 Contemporary Reinterpretation: Heritage as Luxury

Today, after decades of conflict and neglect that have further endangered Baghdad’s built heritage, there is a renewed effort to preserve and revitalize what remains. This takes many forms, from UNESCO-backed reconstruction projects in cities like Mosul to academic initiatives aimed at documenting and understanding traditional environmental design. In residential architecture, there is an emerging trend of re-incorporating traditional elements into contemporary homes. The shanashil, for instance, is reappearing on the facades of new villas, though sometimes in a purely decorative capacity, detached from its original multifunctional role.

This revival has also attracted the attention of the international luxury design market. This signifies a new phase in the life of classic Baghdadi design, where heritage is no longer just a matter of local preservation but has become a source of inspiration for a global clientele. High-end design studios are now engaging with this rich aesthetic vocabulary. Firms like Modenese Interiors, for example, explicitly offer a synthesis of “classic Arabian elegance” and “European… design elements,” using premium materials like fine marbles, gold leaf, and hand-woven fabrics to create bespoke interiors for distinguished Baghdad residences. This trend presents both an opportunity and a challenge. On one hand, it brings investment, global appreciation, and a high level of craftsmanship to the preservation of traditional aesthetics. On the other, it risks de-contextualizing these elements, transforming a holistic and functional design system into a curated collection of “exotic” motifs for a luxury market. This globalization of heritage is the latest chapter in the long and complex story of Baghdadi design.

A Timeless Blueprint for Living

The classic interior design of Baghdad is far more than a collection of aesthetic choices. It is a testament to an enduring architectural intelligence, a sophisticated blueprint for living that has been refined over centuries. Its core tenets—a deep understanding of climate, a commitment to local materials, a profound respect for cultural values of privacy and family, and an integration of intellectual and spiritual pursuits into the fabric of daily life—are woven into every courtyard, every screen, and every decorative pattern.

From the foundational Sumerian concept of the inward-looking sanctuary to the imperial splendor of the Abbasid era and the decorative refinements of the Ottoman period, the Baghdadi house has demonstrated a remarkable capacity for adaptation and continuity. It functions as an elegant, passive machine for creating comfort in a harsh environment, a social armature for structuring family and community life, and a canvas for some of the Islamic world’s most sublime art forms.

In an era increasingly defined by the challenges of climate change, resource scarcity, and cultural homogenization, the principles embedded in this traditional design philosophy have never been more relevant. The Baghdadi house offers timeless lessons in sustainability, human-centric design, and the creation of spaces that nourish both body and soul. It stands not as a relic of a bygone era, but as an inspiring and still-vital model for how to build with wisdom, beauty, and a deep sense of place.